Which factors predict outdoor play in Canadian 7- to 12-year-olds?

Thank you to Dr. Richard Larouche, Associate Professor of Public Health at the University of Lethbridge, for providing this post.

Which factors predict outdoor play in Canadian 7- to 12-year-olds?

Previous studies and literature reviews have consistently found that children who spend more time outdoors are more physically active and generally have better physical, social, mental, and spiritual health than those who play less outdoors (de Lannoy et al., 2025; James et al., 2025). This research is clearly summarized in the 2025 Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play (Lee et al., 2025). Yet, there is consistent evidence showing that today’s children don’t play outdoors as much as previous generations (Bassett et al., 2015; Haidt, 2024).

Study design

To help inform future efforts to promote outdoor play, we assessed Canadian children’s outdoor play time using data from a national longitudinal study involving 2291 parents of 7- to 12-year-olds across Canada (Larouche et al., 2026). Parents were asked to complete the same survey every 6 months until June 2022. We assessed outdoor playtime on weekdays with the following question: “On a typical weekday during the past week, how much time did your child spend playing outdoors?”. We asked a similar question for weekend days. Based on participants’ responses, we categorized children into 2 groups: those who played outdoors less than 1 hour per day and those who played at least one hour per day.

Our survey allowed us to examine factors associated with outdoor playtime at different levels of the social-ecological model (SEM), including individual characteristics (e.g., child age and gender, independent mobility), interpersonal characteristics (e.g., parents’ age and gender, dog ownership), the community (e.g., social cohesion, parental concerns about crime), and the built and natural environment (e.g., parents’ perceptions of the neighbourhood that they lived in).

We also asked participants to provide their postal code, which allowed us to get information about temperature and precipitation during the data collection times as well as objectively measured characteristics of the built environment. Specifically, we assessed park density, blue space (i.e., lakes and rivers) density, greenspace, population density, and intersection density within 1.6 km of the centre of the postal code centroid (i.e., the midpoint of addresses sharing the same postal code).

Results

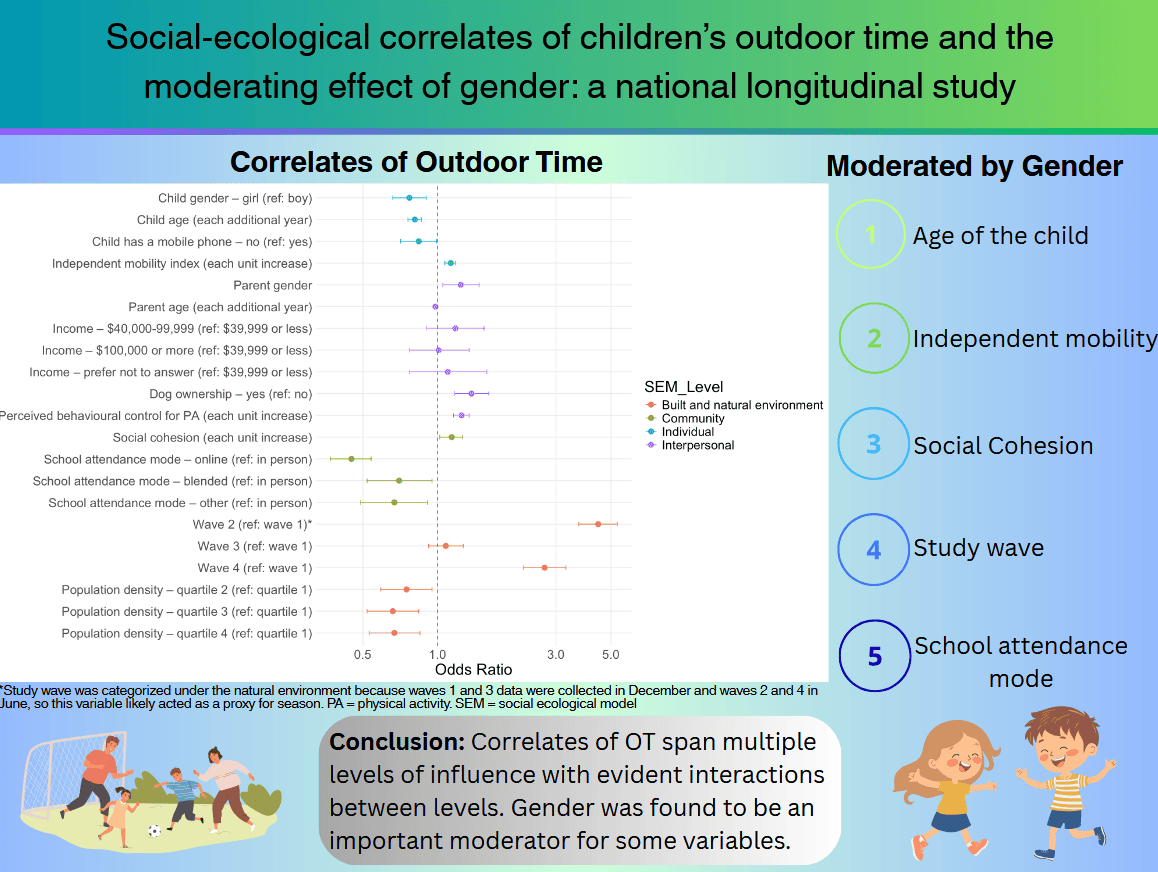

The figure below illustrates all the factors associated with outdoor playtime for each level of the SEM.

At the individual level, we found that girls played outdoors less than boys and that girls’ outdoor playtime decreased more sharply with age. These findings emphasize the need for additional effort to support girls’ engagement in outdoor play, especially among 9- to 12-year-olds. We found that children who had a mobile phone played outdoors less, which supports recent calls to action to reduce screen time to support children’s mental health (Haidt, 2024). Children with more independent mobility (i.e., freedom to explore their neighbourhood without adult supervision) played outdoors more; this was especially true for boys. Yet, independent mobility, outdoor time, and children’s mental health have all declined over the last few decades (Bassett et al., 2015; Haidt, 2024), emphasizing a need for interventions aiming to support children’s autonomy.

At the interpersonal level, parents who owned a dog and and those who believed in their own capacity to support their child’s physical activity reported that their child played outdoors more. These findings highlight different ways through which parents can support their children’s outdoor activities. We also found that children with older parents played outdoor less. While this association was relatively weak, older parents could reap many benefits from playing outdoors with their children (de Lannoy et al., 2025). Lastly, parents who identified as women reported higher outdoor playtime, though it is unclear if this merely reflects differences in awareness between mothers and fathers.

At the community level, children who attended school online were much less likely to spend at least an hour per day outdoors. This association was stronger in girls, likely underscoring the important contribution of recess to outdoor time. Higher parent-perceived social cohesion was associated with more outdoor time, and this association was stronger among girls. This finding suggests that, in more “tightly knit” neighbourhoods, parents may believe that other parents will keep an eye out for their children, and this may increase their willingness to let them play outdoors.

We also found that children living in denser neighbourhoods played outdoors less. While high-density neighbourhoods may help reduce vehicle emissions that fuel climate change (Giles-Corti et al., 2016), urban planners and policymakers should ensure that dense neighbourhoods still provide access to places where children can play outdoors. Lastly, children played outdoors more in summer (June data collection point) than winter (December data collection point). While unsurprising, this finding emphasizes the need to promote winter outdoor activities.

Concluding thoughts

Collectively, our findings suggest that interventions aiming to increase outdoor playtime should focus on multiple levels of the social-ecological model. For instance, our results suggest that parents, school officials, urban planners, policymakers and even dogs influence how much time children spend playing outdoors.

This study provides longitudinal evidence in support of the most recent Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play, which recommends “increasing opportunities for active outdoor play in all settings where people live, learn, work, and play” (Lee et al., 2025).

References

Bassett, D. R., John, D., Conger, S. A., Fitzhugh, E. C., & Coe, D. P. (2015). Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 12(8), 1102-1111.

de Lannoy, L., James, M. E., Badruddin, Z., Thankarajah, A., Bakalár, P., Barnett, L. M., … & Tremblay, M. S. (2025). Association Between Active Outdoor Play and Health Among Children, Adolescents, and Adults: An Umbrella Review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2025-0391

Giles-Corti, B., Vernez-Moudon, A., Reis, R., Turrell, G., Dannenberg, A. L., Badland, H., … & Owen, N. (2016). City planning and population health: a global challenge. The Lancet, 388(10062), 2912-2924.

Haidt, J. (2024). The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Penguin.

James, M. E., de Lannoy, L., Lopes, O., Johnstone, A., Lee, E. Y., Bakalár, P., … & Tremblay, M. S. (2025). A systematic review and meta-analyses of the relationships between active outdoor play and 24-hour movement behaviors. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 101115.

Larouche, R., Duffy, R. T., Larsen, K., Bélanger, M., Brussoni, M., Faulkner, G., … & Tremblay, M. S. (2026). Social-ecological correlates of children’s outdoor playtime and their interaction with gender: a national longitudinal study. Environmental Research, 292, 123625.